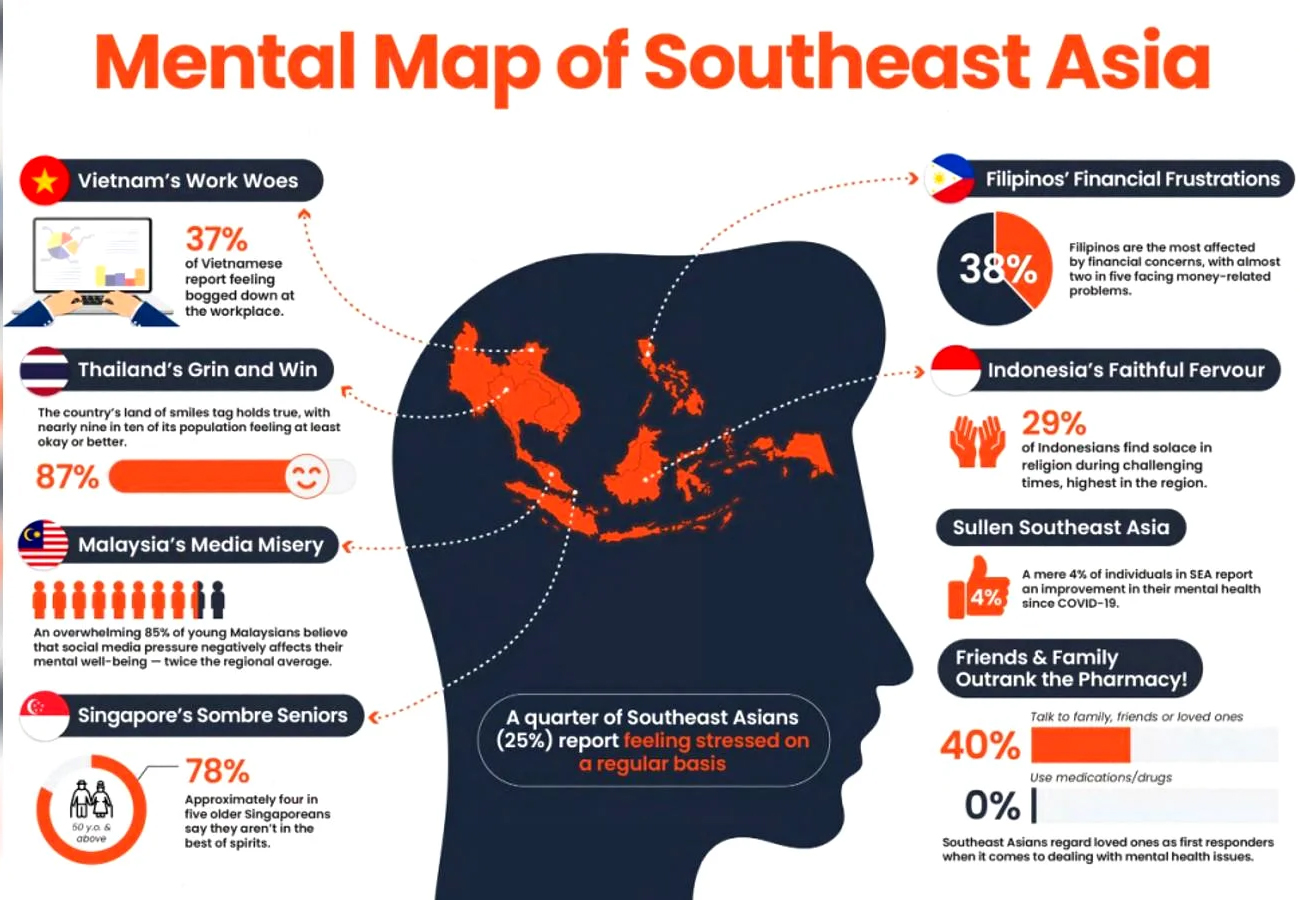

An estimated 13.7 % of the population in the Southeast Asia Region suffers from mental health conditions, while 22 lakh people die by suicide, the WHO said Tuesday

KRC TIMES Desk

KRC TIMES Desk

An estimated 13.7 % of the population in the Southeast Asia Region suffers from mental health conditions, while 22 lakh people die by suicide, the WHO said Tuesday.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) said that the Region sees a treatment gap for mental health conditions, which remains as high as 95%.

Calling on countries to prioritise the transition from long-stay institutional mental health services to community-based care, the world health body said this would ensure that these services are accessible, equitable, and stigma-free and that the affected individuals are provided opportunities to lead a productive life.

People with severe mental disorders die 10 to 20 years earlier than others. However, investment in mental health remains very low across the Region, which also includes India.

“Transitioning from long-stay tertiary psychiatric institutions to community-based care benefits individuals and society. When these services are integrated into the fabric of our communities, it becomes easier for individuals to seek help without the fear of judgment or discrimination,” said Saima Wazed, Regional Director of WHO South-East Asia.

“This shift also allows for greater personal autonomy, improved quality of life, and personalised care options. The community-based settings provide individuals opportunities to regain a sense of independence and engage in social and vocational activities, which can significantly improve their overall well-being,” she said in her virtual address to the regional meeting on ‘Transitioning from long-stay services to community mental health networks: towards deinstitutionalisation in WHO South-East Asia Region’.

She released a report on ‘Deinstitutionalization of people with mental health conditions in WHO South-East Asia Region’, which, while acknowledging the complexities and unique contexts of each country, offers recommendations that can be adapted to local realities.

“This report can catalyse change, igniting a process that results in every person leading a life of dignity, purpose, and fulfilment,” said Wazed, who champions the cause of mental health and has set it as one of her top priorities as Regional Director.

Long-stay mental health institutions, including psychiatric hospitals and asylums, are often characterised by the absence of effective treatment, segregation, poor living conditions, lack of resources, and overcrowding.

The transition from institutional care to community-based care is driven by a growing understanding of the negative impact of long-term institutionalisation, advances in treatments, and recognition of the human rights and dignity of individuals with mental disorders.

“Historically, mental health care has been synonymous with institutionalisation. Large asylums were built to provide a place of refuge for those grappling with mental illnesses. However, as our understanding of mental health has evolved, so must our care methods,” she said.

Earlier, the Paro Declaration on universal access to people-centred mental health care and services, adopted by Member countries of the Region in 2022, and the Regional Action Plan for Mental Health for the WHO South-East Asia Region 2023-2030 emphasised the shift to community-based services.

Besides being more efficient, community-based services are also better equipped to identify mental health concerns early, reducing the need for crisis intervention. This approach benefits individuals, alleviates the burden on emergency services and reduces the overall cost of mental health care, she said.

Importantly, community-based mental health care shows better outcomes, reduces the treatment gap, and increases coverage.

Community-based care models emphasise the creation of safe and supportive living environments within the broader society, which not only benefits individuals with mental disorders but also promotes empathy and understanding among the public, dispelling misconceptions and reducing stigma.

Successful deinstitutionalisation, moving from tertiary care to community care, requires careful planning, collaboration, additional financial resources, and continuous monitoring. It needs parallel expansion of community care services and networks, she said.

Adequate community resources, including housing, employment opportunities, vocational training, empowerment of people with lived experience and caregivers and social support networks, must be established to facilitate a smooth transition from institutional care and integration and reintegration into community living.

Comprehensive training programs for mental health professionals, law enforcement, educators, and community members are essential to ensure that individuals with mental disorders are treated with respect and understanding for their full inclusion and participation in communities.

The process of deinstitutionalizing is a complex undertaking that requires careful consideration of cultural, social, economic and policy factors, she added.